Death, Dying, and a Pervasive Anxiety Over the Unknown

I am absolutely terrified of death. The moment of death. The moments of decline leading up to it. And ultimately, the moments leading up to the decline that in some fashion all feel for naught, knowing that one day memories will have faded, your name will no longer be said, and the sun will scorch our earth lifeless.

I am absolutely terrified of death. The moment of death. The moments of decline leading up to it. And ultimately, the moments leading up to the decline that in some fashion all feel for naught, knowing that one day memories will have faded, your name will no longer be said, and the sun will scorch our earth lifeless.

Existential buffoonery or not, the sense that life is futile is a plague that's run deep in me from the time I can remember. At age five I wrote my first poem, an allegory about a boy who lost his yellow mitten in the snow. The boy dug for hours and hours through the snow to no avail, the woefulness of his efforts compounded by the knowledge that the mitten lay somewhere beneath an attempt not yet explored.

At age six I began questioning the tenets of my Christian faith. If God can do anything, and God wanted to make "nothing" exist, what would that look like? Isn't emptiness, blackness, only the presence of God, something? I had concocted my own can God make a rock so big he can't lift it scenario.

At age seven I woke my parents late at night, having spent hours crying while coming to terms with the fleeting nature of memories as the Care Bears soundtrack played through my head:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9r_wBgRuDco

As you can guess I was the at the top of everyone's birthday party invite-list.

But no matter how much existential angst I had about leaving this place, I took comfort in one important detail. And I had that detail dead wrong.

I believed that when you left this earth, most people went peacefully in their sleep, and it was the unlucky few for which the process was drawn out, painful, and humiliating. But as it turns out, it's the exact opposite.

Last week my grandmother, Bette Powers, died just a month shy of turning 92. No one doubts that she lived a rich, full life. But just as I saw with my grandfather pass before her, her death was one of pain and anguish, punctuated by failures of the body and bedpans.

A 90% blockage of her carotid artery led to a massive stroke, which in turn paralyzed her entire left side, reduced her speech to little more than intoned slurs and moans, and most importantly left her completely unable to eat or swallow. But she was 100% lucid, a prisoner of her own body.

At 90 years old my grandmother was still driving. Grocery shopping. Paying her bills online. And had mastered checking her Facebook from her iPad.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=voJy5aUz_Oo

But now my grandma lay in a bed, communicating through hand gestures, pointing at pre-written phrases, and astonishingly through her own penmanship which remained without question better than mine.

Her tongue hung out of her mouth, inoperable and off-white as it turned to bacterial flakes snowing on her gown below.

After an excruciating 15 days without food and 8 without water, my grandma finally went. She left the exact minute my plane touched down at SFO, on my way to see her.

Fortunately, the week prior I was able to take time off work to fly from Chicago to the Bay Area and hug and speak to her. When I told her that I had to leave but that I'd be returning next week, she begged me not to go. "I don't want to die," she pleaded. She bawled with the helplessness of a baby but the recognition of a woman who'd seen 92 years of life being pulled away from her. It's a haunting sound I hope never takes lodge in my brain.

And it's these moments that make even the great nothingness death reveals into something huge and cruel. A game we never asked to play in which we're forced to lose.

No sweaty palms at flight takeoff. No nudge in my gut that wonders if cancer looms. No check engine light or early warning sign will ever be enough to kick the can of death off the road entirely.

And at 31-years-old that scares me just as much as it did at five.

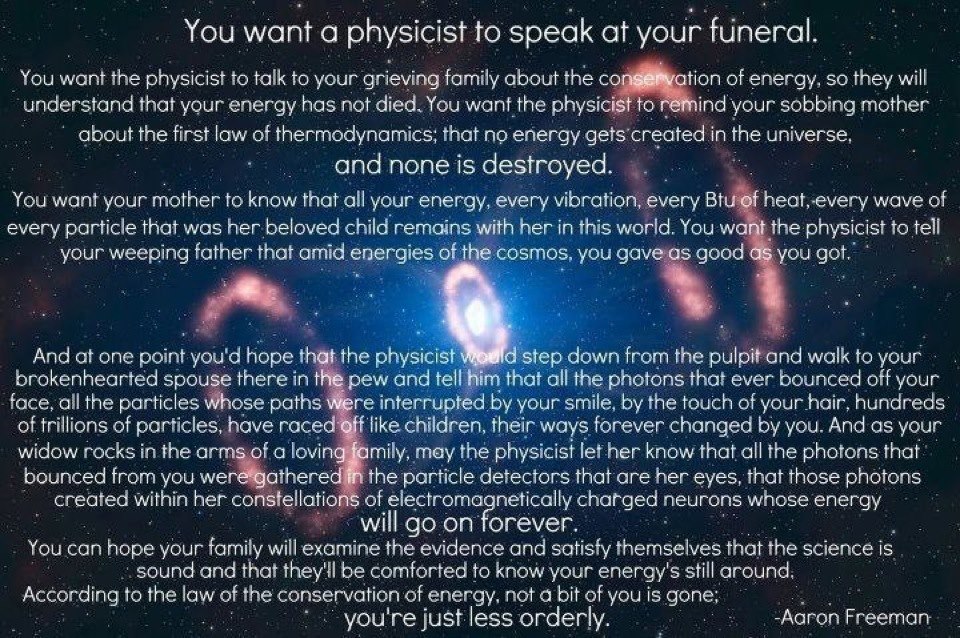

When my grandpa died four years ago, I took some degree of solace in a quote I had read from writer Aaron Freeman:

The science of what we are truly did help. It was an answer to the void left by my Christian faith.

But perhaps more important is the science of who we are. How every smile, every gesture, every particle touched is indeed another person moved, moved to pass on that which you have brought into their path.

And maybe as the world fills with these thoughts and gestures of love and positivity, they will surround us in our dark moments of death. And maybe it's possible that one day, the multiverse will become so inundated with this energy, that it will spill into an even greater beyond of which we not yet know.

Either way, I'd be lying if I said I'm not scared, overwhelmed by what horrors of beauty may await.